The Isthmus of Panama

(photo credits: Madereugeneandrew, Southbound on the Panama Canal approaching the Centennial Bridge, CC BY-SA 4.0)

In Panama, the shores of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans are only about 60 km apart.

The Panama Canal uses this unique feature of the Isthmus of Panama. It allows ships to go from the Caribbean Sea to the Pacific without sailing around South America.

While the canal opened more than 100 years ago, the Isthmus of Panama is a key site in global transportation for more than 500 years now.

With different routes across the jungles of Panama, it played an important role in the Spanish World Empire, the development of the United States of America and 20th century globalization.

This article shows the history of crossing the Isthmus of Panama and the different routes involved.

Content

Spanish Routes

California Gold Rush and the Railroad

Building the Panama Canal

The Isthmus of Panama in last 100 Years

Interactive Map of the Isthmus of Panama

– Map markers have pop-up windows with additional information. – Map controls: buttons for zoom and fullscreen in top left – keyboard zoom with +/- keys as well – Map layers: change between terrain and classic OSM in top right.

(Feel free to click on the map marker. Pop-up windows will open showing pictures and additional information.)

Spanish Routes

In 1513, ten years after the first European ships sailed along the Isthmus of Panama, Spanish explorer Vasco Núnez de Balboa put together an expedition to cross the Isthmus. He had heard about the Ocean on the other side of the land bridge and all the gold to be found there.

His party of more than 100 Spaniards were the first Europeans to learn a key feature about the Isthmus of Panama – it is a tropical jungle.

The expedition struggled for four weeks with torrential rain, disease and a difficult landscape without any paths. They covered a distance of about 100 km in the south of Panama near today’s border with Colombia before they reached Pacific Ocean.

Balboa’s expedition was a success. He found gold, heard rumors about more gold and discovered a new ocean to explore.

Without a – literal – way to access the newly discovered ocean, all this however could not be exploited.

Camino Real

The year 1519 is therefore an important milestone: A city on the Pacific Ocean was founded – Panama – and a road was built to link it to the existing port in Nombre de Diós on the Atlantic shore.

4,000 natives were forced to work on this track which was about 80 km long, about one meter wide. It was partially covered with stones and river crossings were facilitated with simple log bridges. While this was little more than a jungle path, this Camino Real was the key infrastructure that enabled the Spanish to fully conquer and exploit Central and South America.

Since the early strategy of the Spanish was one of plundering, soldiers and weapons went one way across the Isthmus of Panama and all the preciosities that they stole could be carried the other way. There were no large volume goods for which the basic trail was not sufficient.

About ten to fifteen years later the Camino Real was supplemented by the Las Cruces Trail. This jungle trail was about half the length and went from Panama to the settlement of Las Cruces on the Chagres River.

For the second half of route across the Isthmus of Panama the Charges River was used. People and goods were transported on simple boats to the Caribbean Sea at San Lorenzo.

Both routes are shown on the map. “1” marks the approximate route of the Camino Real. “2” shows the Las Cruces Trail from Panama to Las Cruces and the remaining part of the Chagres River below the Gatún Dam.

Silver from Potosí

Panama was the base for Spanish activities on the Pacific Coast of South America. After the initial exploration, conquistadors like Pizarro discovered and conquered the Inca Empire in 1531/32. All gold and silver plundered from the Incas was transported through Panama, across the jungle paths to Nombre de Díos and by ship to Spain.

But this was only the beginning of the Isthmus of Panama as the most important transshipment hub in the Spanish Empire.

In 1545, not long after the conquest of the Inca Empire, the town of Potosí was founded in the remote highlands of Bolivia. It was the mining settlement for the Cerro Rico – the rich mountain – the world’s largest silver deposit. For more than 200 years, it was mined extensively and the silver made its way through Panama. Caravans of mules and llamas made the 700 km long journey to the port of Arica in what today is Chile. From Arica it was shipped around 5,000 km to Panama.

Here storehouses and mule stables were built for the transport across the Isthmus.

Around 1600, when the silver flow reached its peak, 8 million pesos (25 gram each) were shipped through Panama. This is an amount of 200 tons and 2,000 mules are required to carry this cargo.

The Treasure Fleets

Once a year a fleet would sail from Cartagena in Colombia to Nombre de Dios then to Havana in Cuba an across the Atlantic to Spain. This treasure fleet collected all the riches of the Americas and was an early example of a convoy system as heavily armed warships accompanied the galleons that carried the precious cargo.

When the fleet arrived back from Spain in Cartagena, messages were sent to Panama and silver transport across the Isthmus of Panama started. The mule caravans transferred their silver onto the galleons anchoring at Nombre de Dios adding to the goods from Colombia.

The fully laden ships sailed to Cuba where they met with a treasure fleet from Mexico and then made the trip back to Spain.

The Treasure Fleet system of the Spanish Empire was a truly global transport network and the Isthmus of Panama was an integral part of it.

The first fleets were organized in the 1560s and continued to sail for more than 200 years.

I am happy to hear from you,

Jens“

(photo credits: Garcia.dennis, Toma aérea del Fuerte San Lorenzo, CC BY-SA 4.0)

(photo credits: Joseph vasquez alen, Puente del Rey–, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Pirates of the Caribbean

The enormous values that Spain extracted from South America and shipped across the Atlantic soon attracted competition. Other European states began to establish plantation colonies in the Caribbean but more importantly piracy became a threat to the treasure fleets.

With the heavily armed and escorted treasure fleet itself, attention turned to the transshipment points on the Isthmus of Panama. Nombre de Dios and Portobelo were raided several times by famous pirates such as Francis Drake or Henry Morgan. Drake also captured a mule train on the Camino Real but could only carry away a small amount of the gold and silver.

Even the fortified city and depots on the Pacific side in Panama were raided and destroyed by Henry Morgan in 1671, which led to the foundation of Panama City at its current location a few kilometers south west of the old site.

The Spanish reacted by fortifying Portobelo and the mouth of the Chargres River at Fort San Lorenzo. These buildings together with Old Panama are part of the UNESCO World Heritage showing the importance of the Isthmus of Panama.

The Spanish Infrastructure

The Spanish routes across the Isthmus of Panama were part the global silver transshipment system for more than 200 years. Treasure fleets sailed from the Isthmus until 1790, when the Spanish government ended monopoly trade with the Americas.

About 20 years later, as a result of the Napoleonic wars, the Spanish colonies in South America revolted and became independent states. Panama declared independence in 1821

The Isthmus of Panama with its caravans system was mainly designed for preciosities like gold and silver. High volume goods like the output of the plantations in the Caribbean could hardly transported on the isthmus.

The jungle tracks and rivers of Panama were also not well suited for travelers to cross the Isthmus. As we will see, this however became the focus in the mid-19th century.

California Gold Rush and the Railroad

US Expansion

After being controlled by the Spanish Empire for more than 300 years, the Isthmus of Panama came under the influence of a new power emerging in the Americas itself.

The United States saw major demographic and territorial expansion in the 19th century. The Louisiana Purchase and the Florida Cession brought the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi/Missouri Basin under their control. By the mid 19th Century, the Pacific Coast was added as a result of the Mexican-America-War (1846-1848) and the Oregon Treaty (1846) with Great Britain.

The vast territories were however far away from the centers of population on the East Coast. Beyond the Mississippi and Missouri rivers with its riverboats there were only a few trails leading further west across the plains and the Rocky Mountains. These trails like the Oregon Trail or the Santa Fé– and Old Spanish Trails had no infrastructure and became famous for their self sufficient settler wagon trains. The transcontinental railroads were still 20 years in the future, with the Pacific Railroad making the link in 1869.

With the acquisition of the Pacific Coast of North America, the Isthmus of Panama draw the attention of US policy and business for a shipping route to California and Oregon. The US secured transit rights on the Isthmus from the state of New Granada (today Columbia) under the Mallarino-Bidlack Treaty in 1846 and started to organize a mail service between New York and San Francisco by steamers (New York-Chagres and Panama-San Francisco) and railroad (across the Isthmus of Panama).

California Gold Rush

The steamships went into operation late in 1848 just as gold was found in California. The gold rush then hit the Isthmus fully unprepared. Fortune seekers arrived in Chagres from the East Coast in large numbers but by the mid-19th century no infrastructure existed on the Isthmus. The old Spanish trails had been reclaimed by the jungle and only few dugout canoes existed for local trade on the Chagres river.

In these chaotic situation, everybody wanted to be the first on the other side on the Isthmus of Panama and ultimately the first to stake a claim on the gold fields of California. People tried desperately to find a way through the tropical jungle as the first Spanish explorers did 350 years before. Most of them gave up and paid the ever rising price for a trip in a dugout canoe to Las Cruces.

The Las Cruces trail to Panama had not been used for about 50 years and also been overgrown by the jungle. Here however, it was soon re-established and the remaining way to Panama was easier to complete. There, people fought for a place on a steamer to San Francisco the last leg of their long journey.

Even before the railroad was completed, the journey by steamer and across the Isthmus of Panama was faster than the overland trek. It took around 8 weeks (6 weeks, once the railroad was in operation) compared to around 6 months on the trek across the plains and the Rocky Mountains.

After the initial chaos of the gold rush was overcome, the Isthmus route was the easy and safe option and greatly assisted the early development of California.

Building the railroad

Work on the railroad started on 1850 with the construction of dock facilities and a worker settlement on the site what today is Colón. Former Manzanilla Island and the first good 10 km of the surveyed route were a tropical swamp. Work was slow, costly and dangerous. Docks and buildings had to be built on piles and the the route backfilled with rocks.

Workers came from all over the World – the Americas, Europa, China – and many died from tropical diseases, which were not understood at the time. There are no good records of the death toll. Estimates are between 5,000 and 10,000 deaths during the whole construction period of the railroad.

In late 1851, after more than a year, the railroad reached the Chagres River near Gatún. By this time the company’s initial funds of one million US dollars were expended and the financial situation saved by offering the first passenger service between Colón and Gatún, which shortened the boat journey on the Chagres River considerably. This also shifted the shipping from the mouth of the Chagres River, where no dock facilities existed, to Colón (which was then called Aspinwall – after the railroad co-founder).

Work along the Chagres River continued, extending passenger service along the way. The main river itself had to be crossed at Barbacoas. River crossings, especially of the Chagres river itself, had to consider the huge amount of rainfall. This could lead to rise the river by more than 10 m and bridges had to be high and robust enough. The building of the Barbacoas bridge was completed in late 1853. It was was almost 200 m long and 15 m above the normal level of the Chagres River.

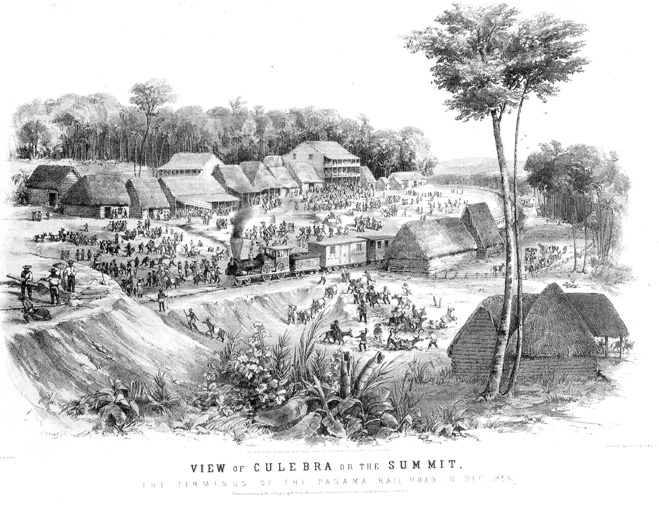

The last major obstacle was the the summit near Culebra. Several months of digging to lower the ridge were spent in 1854 until the lines from Colón and the second line, which was built from Panama, met at the summit. The official last spike was driven in January 1855. 76 km of rail now reached over the Isthmus of Panama allowing to cross in about four hours.

A new route across the Isthmus of Panama

This was a major achievement not only for the American passengers, looking for a transcontinental passage to California. In terms of the history of the Isthmus of Panama itself it was a huge step from dugout canoes and mule trails in the jungle. These were barely suited for passengers and high value goods. With the railroad bulk transport became feasible with port facilities at Colón and Panama on both shores.

The construction costs were eight million US dollars and thus exceeded the initial estimates eightfold for a route of only 76 km. The tropical climate had been completely underestimated.

The climate itself ate away most wooden constructions really quickly. Therefore, after line was completed in 1855 with a clear focus on becoming operational, work did not stop. Wooden bridges were replaced by stone and steel. Wooden sleepers were replaced with lignum vitae, a tropical hardwood that does not decay in the jungle.

(photo credits: Fessendon Nott Otis, Colored lithograph by Charles Parsons, Culebra Summit Panama Railway, marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons)

(photo credits: Adam Jones, Train of Panama Canal Railroad Company Speeds Past, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The railroad service continued to be profitable after the gold rush and throughout the 19th century. Soon, its history becomes mixed with that of the canal itself.

The presence of a railroad was one of the factors to favor the Isthmus of Panama as the canal location over other routes (such as Nicaragua).

The Modern Railroad

Once the canal was completed however in 1914, the railroad went into a long decline as it lost relevance.

This was only changed in 2001, when a large upgrade was completed. This involved changing the gauge and thus essentially a new railroad.

It was built new with a clear focus on container traffic, while operating commuter passenger services. There are inter-modal container terminal on the line at Colón and Balboa. Between these the trains shuttle containers in double stack railway cars.

The capacity is at around 1,500 containers per day, which is around 5 % of the capacity of the canal. The target for the railway shuttle however is not the intercontinental shipment of containers but more the local collection and distribution between the Pacific and Atlantic coasts.

Building the Panama Canal

With an existing railroad across the Isthmus of Panama, ideas to build a ship canal became plans. The success of the inter-modal railroad crossing increased the demand for a ship-only route. Canals were an established infrastructure in the 19th century and strategic canals were being built. The Erie Canal and the Illinois and Michigan Canal were key links in the waterway system within the US and completed in 1825 and 1848, respectively.

The most prestigious project however was the Suez Canal, which was started in 1859. For the British Empire it played a similar role as the Panama Canal for the US – it cut out sailing around a whole continent to reach either India or California.

The French Project

The French success in Suez encouraged a similar project in Panama. The 1870s saw the surveying by French engineers, the creation of a company and a concession by Columbia to build a canal across the Isthmus.

The man who led the Suez venture to completion, now was in charge of the Panama project. Ferdinand de Lesseps, 76 years old when the digging started in Panama in 1881, a French diplomat with extensive experience in the Mediterranean and Arabic World.

He had no engineering expertise, visited Panama only in the dry season and was fixed on copying the Suez plans for implementation on the Isthmus.

The Suez Canal however, is a sea level canal with no locks, dug through a flat, sandy plain. The Isthmus of Panama posed completely different challenges. The mountains of Panama were only 110 m high at the lowest point but this rocky spine had nevertheless to be cut. The rivers of the Isthmus became torrents in the rainy season. They would be dangerous to ships in the canal and would have to be channeled away from a sea level canal.

Tropical Diseases and bankruptcy

Technological advances in the 19th century might have been able to overcome these challenges. One thing however did not change from the days of the early Spanish explorers. Tropical diseases made life and work in Panama unhealthy at best and deadly for many.

Just like the Panama Railroad, the French canal project brought death to many people. The estimate for the eight years from 1881 to 1889 is at more than 20,000. Malaria and yellow fever were the main reason and there was no way to fight them in the 1880s.

What brought the activities to a hold in 1889 however, where probably more the engineering issues like mudslides combined with financial problems. Progress in Panama was hampered by de Lesseps’ hesitation to move away from a sea level design.

When money finally ran out it became known that the company had bribed politicians to conceal their problems from the public. A major scandal erupted in France.

Transition Period from 1894 to 1904

A successor company was set up in France in 1894 with a new concession from Columbia. However, this became more of a shell company to maintain the dig and the equipment, hold on to the concession and find a buyer.

The French companies had removed around 60,000,000 m3 by the time the project was sold to the US. The estimated excavation volume for the French sea level canal was 120,000,000 m3.

Once the canal was complete in 1914, a total of about 205,000,000 m3 were excavated – and this was an elevated canal with locks, which required less digging as the proposed French design.

The French canal also completed approach channels dredged to Balboa on the Pacific and inland from Colón towards Gatún.

The US Project

It was this overall package that was acquired by the US in 1904. As Columbia would not agree to the initially proposed terms of a concession, the US encouraged and supported rebels in the Panama province of Columbia to declare independence in exchange for the canal deal. Thus Panama became independent with US naval support and came under US influence with the canal zone being US territory until 1979.

The time between 1904 and 1907 was spent with assessing the existing works, settling for a lock design in 1906 and preparing the Isthmus for major construction activities. To the advantage of the US, the role of mosquitoes in transmitting malaria and yellow fever had been understood at the time. Under William C. Gorgas as chief sanitary officer the century-old problem could be addressed. The loss of life therefore could be limited to around 5,500 in the time to 1914 on a project with 40,000 workers at peak times. This still amounts to more than one person dying every day for the time of the US construction.

The Panama railroad was an instrumental infrastructure in building the canal. It transported the excavated material away from the site, transported equipment and workers.

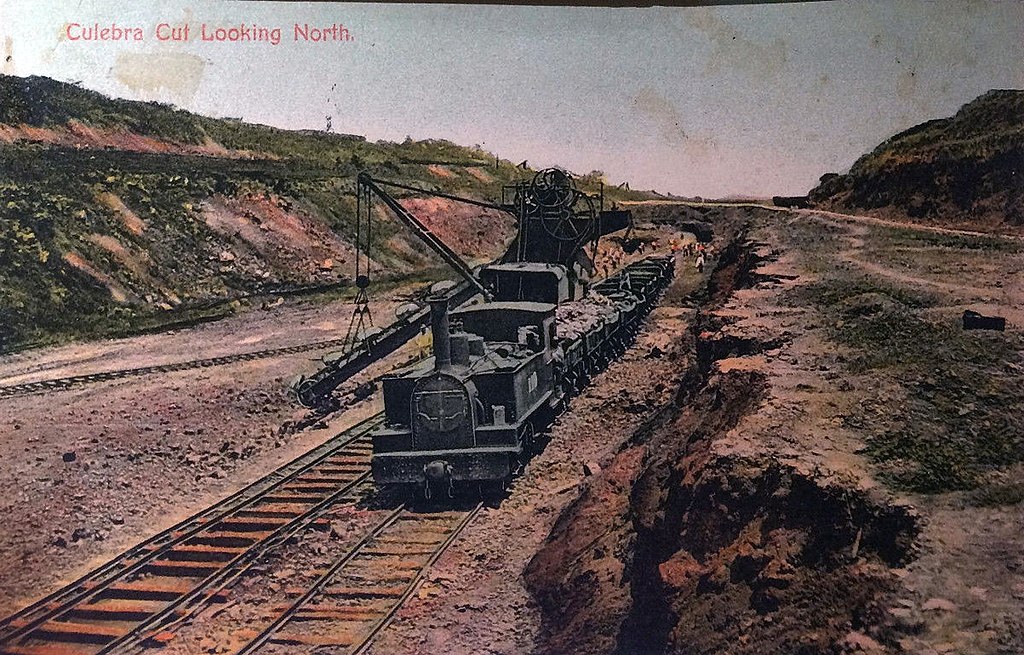

The mountains at Culebra were lowered from 110 m above sea level to only 12 m. The cut had to be widened over the original French assumptions and slopes lowered as landslides posed a problem with the ground softened by dynamite and tropical rains. The railroad was helped in this task with modern steam shovels but still digging lasted for around 6 years from 1907 to 1913, while Gatún Dam and the locks were built.

(photo credits: Trainiac from Australia, Panama Canal (45902863324), marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons)

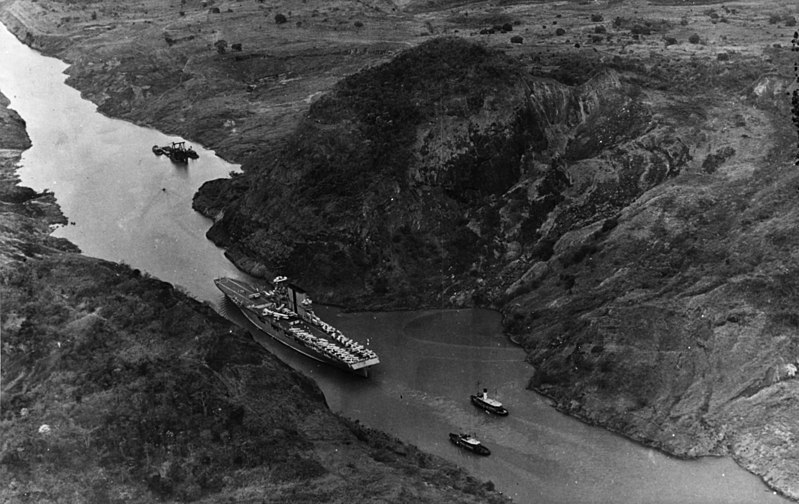

(photo credits: Chief Photographer John Lee Highfill, U.S. Navy, USS Saratoga (CV-3) transiting the Panama Canal on 4 March 1930 (NH 95035), marked as public domain, more details on Wikimedia Commons)

(photo credits: Andre Pantin, 03-057 Esclusas de Gatún – Flickr – Andre Pantin, CC BY 2.0 )

The railroad itself had to be re-routed as well. The original line along the Chagres river was to be become part of Gatún Lake. The loop away from the shipping line east of Gatún Dam and on causeways just above the waterline of the lake and towards Gamboa were built on a new route. The Bridge at Gamboa across the enlarged Chagres River did not exist before and landscape around the former summit at Culebra was completely transformed by the canal as well. But not only the route was completely new. The tracks were improved to serve heavy rail-cars and stronger engines.

The canal was flooded in October 1913 with a telegraphic signal from US president Wilson. On 07. January 1914 an old French construction vessel, the Alexandre La Valley, was the first ship to sail the entire length of the canal. The official opening for mid 1914 were canceled as the crisis and Europe and the outbreak of the First World War overshadowed events. The official first transit was made by SS Ancon on 15. August 1914.

The Design of the Canal

The canal that was built between 1907 and 1914 is still in operation today. The canal is 26 m above sea level. This waterway was constructed by blocking the Chagres River at Gatún with the Gatún Dam generating the large Gatún Lake, which flooded the lower basin of the former river. Gatún Dam is the spillover for the lake, which still gathers tropical rainfall from the Chagres drainage basin. Further upriver the Chagres is dammed to form Alajueja Lake, which serves to control water levels of Gatún Lake.

The watershed towards the Pacific was cut as Culebra. On the Pacific side the canal has two sets of locks, Pedro Miguel and Miraflores with the Miraflores Lake at 16 m above sea level in between.

The Atlantic side has locks at Gatún to reach Gatún Lake. All locks have two lanes.

Beyond the locks, there are harbor facilities at Colón on the Atlantic and large breakwaters that shield Limón Bay from the Caribbean Sea. These were filled with excavated material from the canal. After construction of the canal was completed, artillery batteries were built there to defend the canal entrance.

On the Pacific, the main harbor is at Balboa on the approach channel to the canal and also here a large breakwater was constructed, which includes small islands off shore.

The Isthmus of Panama in last 100 Years

The long held dream to sail across the Isthmus of Panama became true and the canal proved to be important to the US economy and Navy.

The strategic impact be most obvious in the Pacific War with Japan. After much of the fleet was destroyed in December 1941 at Pearl Harbor, the Panama Canal helped to quickly reinforce the Navy in Pacific.

Adapting to more traffic

The more constant commercial traffic increased over time.

In 2018 it was at an average of 1,000 ships per month or 33 per day. The transit time is 8-10 hours. Ships can sail under own power but need a pilot. They are assisted by tugboats and ‘mules’ in the lock chambers. These electric locomotives move ships in and out of the locks and protect the locks against damage from the ships by guiding and holding them in position.

Additionally, ships increased in size since the early 1900s as well.

While the key features of the canal that was completed in 1914 are still in place, improvements to increase capacity and ease of operations were done throughout the last century. While organizational improvements mainly addressed the increase in the number of ships, ships grew bigger as well. Therefore, more tug boats were added, the approach channels on either side deepened, the navigational channel in Gatún Lake deepened as well as Culebra Cut widened and straightened. This crucial location had to be restricted to single-traffic for larger ships before.

Canal Expansion Project

The key restriction however, remained in place. The locks determined the maximum size of the ship’s hull. This size became known as Panamax and became a risk for future success of the canal. Panama held a referendum in 2006 over the question to build a third (larger) set of locks on the canal. It was approved by the citizens and construction of this key improvement since 1914 was completed in 2016.

In addition to the larger locks, the project included new access channels to the locks and a water saving systems for the locks. The previous locks took the water that was needed to raise or lower ships in the locks from Gatún Lake and it flowed out into the oceans. In the dry season this brought the water supply of Gatún Lake and Alueja Lake to a limit. The new locks do not let the water flow away. If a ship is lowered by emptying the lock chamber, this water is channeled to a water saving basin and can be used again for the next ship traveling upwards. Each lock has 3 of these chambers and can save 60 % of the water needed.

By increasing the locks chambers, the new locks – Aqua Clara on the Atlantic and Cocoli on the Pacific – set a new standard for ship sizes: New Panamax.

Compared with Panamax these are:

Length: 366 m now, 294 m before

Width: 51.25 now, 32.3 m before

Draft: 15.2 m now, 12.0 m before

For container ships, this means 13,000 TEU (standard container units) on NewPanamax ships as compared with 5,000 TEU on (Old)Panamax ships before.

Transit statistics

Container ships are currently the top category of ships transiting the canal per year as of 2018 (2,600). Next come dry bulk carriers for grains, minerals, etc (2,500) and tankers for chemicals (2,000). These categories make up 60 % of all transits.

Historically, the canal was driven by the need for a connection of the US East and West coasts. Today, shipments on this route make up 3 % of the goods moved through the canal.

Traffic from the US East Coast to Asia makes up 31 %, additional traffic from the US East Coast to Pacific destinations in Central and South America 21 %. Traffic between destinations in Central and South America generates 10 % of goods comparable to the traffic of Pacific destinations with Europe at 12 %.

Conclusion

This data shows that demand for the strategic location that the Isthmus of Panama still is has changed over time.

While it was primarily used by the Spanish to exploit Central and South America and ship its preciosities to Europe it was then used by the US as a substitute for internal infrastructure. Today, with Central and South America as well as Asia taking active part in a global economy it became a true location for global transportation.

It has incorporated new technologies over time changing the Isthmus dramatically but it stayed relevant for more than 500 years now.

It is fitting with this development that Panama took full control of the canal in 1999 under the Torrijos-Carter treaty ending long periods of external influence on the Isthmus.

Then sign up for our free email newsletter to get quarterly updates right to your inbox.

I am in Panama staying at the Hyatt Hotel, Calle 52 Downtown Location. I am here to Register for the Ocean Policy and UNCLOS/IUCN platform at the Maritime University but nobody seems to know anything about this course.

It is quite interesting as the Panama Canal celebrates its 100year of existence. It is wonderful that the sea routes and the increasing trade activities with South America brings us closer to this connection between Central and South America.

The revision of UNCLOS in the year 2018 and the paradigm shift to the Compliance of these Clean Policy for seafarers and ocean management of the Habitats and the flora and fauna Species like the Pacific Whales and the dolphins of the Orinoco become important for protection and preservation.

Ocean Policy is the United Nations focus from 2021-2050

Hi Rosemarie,

Thank you for your comment.

I am glad you found your way here.

I see this website as my contribution to raise awareness about our maritime heritage.

Kind regards

Jens

On your web site: The steamships went into operation late in *****1948******** just as gold was found in California. this is incorrect you meant 1848. please correct. thanks.

thank you for this web site as I was just writing about my 3rd gr. grandmother who came by the isthemus of Panana.

Pamela Harter

Hi Pamela,

Thanks a lot for pointing out this typo!

I am glad that you find the website helpful and that it helps you to learn about your family’s history.

Best regards

Jens

My great grandmother also came to San Francisco in 1852 from the East Coast of the US. She and her first husband took a coaling ship, Clarissa Andrews, from Panama to San Francisco.

Hi Sharon,

Thank you for sharing that piece of family history.

The Panama railroad was not complete at that time. It must have been quite a journey!

Best regards

Jens