We look down Menenstraat towards the center of Ypres from the same position at Menin Gate 100 years apart. Behind us, the street crosses the rampart and moat of the old fortifications and leaves the town towards Menen.

Narrow, three-story brick houses line the cobbled street. It leads to the famous Gothic cloth hall – only 200 m away but hidden from our view by the slight bend in the street. It is a scene in a typical medieval Flemish town. Today cafés and bars alternate to occupy the ground floor of the brick buildings with the odd Belgian chocolate shop sprinkled in between.

What seems to indicate continuity in this view is deceptive however. Centuries-old buildings in a small, sleepy country town in Flanders is not what we are looking at today.

Ypres is not your average Flemish country town and Menin Gate not a random street corner to indulge in picturesque architecture.

Looking down Menenstraat again in 1919 gives us an idea why.

Half a year after our first picture was taken, Ypres found itself on the Western Front of what would be called the Great War. The German army occupied the hills outside the town and their artillery fire reduced the medieval city to ruins.

The British army held Ypres during the years of the war. They died in the Ypres salient by the hundred thousands – just as the opposing German soldiers. Most of them are buried in cemeteries, dotting Flanders fields today just like the poppies on the fresh graves in John McCrae’s poem.

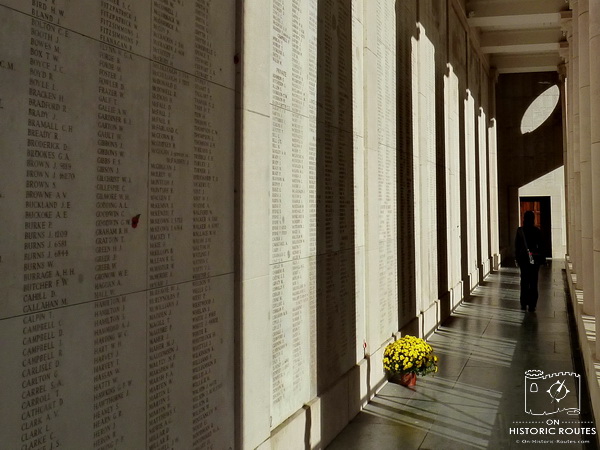

The devastation delivered by artillery, poison gas, mines and machine guns left many corpses beyond recognition or simply missing altogether.

To commemorate them, the British government built the Memorial to the Missing at Menin Gate. It was completed in 1927 and it is this hall-like structure that frames our current view down Menenstraat.

Ypres not only looked into the abyss of war, it was in the middle of it and returned.

The old buildings were reconstructed and almost fool us today for being original.

Life came back to Ypres and remembering the horrors of war became a new tradition. The restored cloth hall now houses the excellent ‘In Flanders Fields‘ museum and Menin Gate is one of several somber memorials to futile death in the Ypres salient.

Menin Gate speaks to us silently most of the time. It does that by the sheer weight of the almost 55,000 names on its walls. Everyday at 20:00 however, Menin Gate changes character.

The street is blocked off by the local police, buglers appear, march in position and play ‘Last Post‘ inside Menin Gate. It is a brief yet very moving ceremony. After a few minutes the buglers salute, march off and hop on their bikes to cycle home.

The Last Post Association is a local Ypres organization that holds this ceremony every day since 1928. More than 31,000 Last Posts have been played at Menin Gate.

The ceremony started to commemorate the sacrifice of British soldiers in defending Ypres. Today it evolves to include all soldiers on both sides of no man’s land.

The Great War never left the Ypres salient but today it is the shared heritage of a united Europe and no longer one of personal and national suffering.